Title

Intrada (1947) For trumpet in C and piano Arthur Honegger (1892-1955)Biographical Info

There is a website that has an exhaustive biography of Arthur Honegger. Below, I’ve included just the highlights.

Arthur Honegger was a Swiss composer, who lived a large part of his life in Paris. He was a member of Les Six. His most frequently performed work is probably the orchestral work Pacific 2311, which imitates the sound of a steam locomotive.

Born Arthur Oscar Honegger in Le Havre, France. He initially studied harmony and violin in Paris, and after a brief period in Zürich, returned there to study with Charles Widor and Vincent d’Indy. He continued to study through the 1910s, before writing the ballet Le dit des jeux du monde in 1918, generally considered to be his first characteristic work.

Between World War I and World War II, Honegger was very prolific, composing nine ballets and three operas, amongst other works. One of those operas, Jeanne d’Arc au bûcher (1935) is thought of as one of his finest works.

Honegger had always remained in touch with Switzerland, his root country, but with the outbreak of the war and the invasion of the Nazis, he found himself trapped in Paris. He joined the French Resistance, and was generally unaffected by the Nazis themselves, who allowed him to continue his work without too much interference, but it is said that he was greatly depressed by the war. Nonetheless, between its outbreak and his death, he wrote his last four symphonies (numbers two to five), which are quite frequently performed and recorded.

Arthur Honegger died on November 27, 1955 and was interred in the Cimetière Saint-Vincent in the Montmartre Quarter of Paris.

Although Honegger was a member of Les Six, his work does not typically share the playfulness and simplicity of the other members of that group. Far from reacting against the romanticism of Richard Wagner and Richard Strauss as the other members of Les Six did, Honegger’s mature works show evidence of a distinct influence by it.

Suggested Equipment

C trumpet, no mutes.

Wynton used a Bb on his “Music on the 20th Century” CD and I played it on a recital on a Bb a long time ago. I guess for me it comes down to I would rather play a high C on a C trumpet than a high D on a Bb.

Practice/Performance Tips

There are so many great recordings of Honegger’s Intrada available. I strongly encourage you to get acquainted with a few and develop your own opinion to the interpretation. Here are a few thoughts I’d like to share based on issues that have come up in my own preparation and when working with students on this piece.

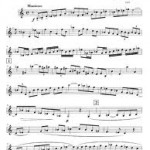

Notice in the opening three measures how every other note is preceded by a half step. One could use these somewhat as leading tones to create more direction in the line. In the following clip I play the first three measures in three different ways. 1. All notes equal = no particular direction. 2. Just every other note = the “goal note” of the preceding grace note, or the core melody. 3. Phrasing with the core melody in mind.

One of the big issues in this piece is figuring out where to breathe. (Honegger goes from measure 4 through 17 without any rests or breath marks!) In this next clip I offer two breathing suggestions. The first pass makes the most sense to me musically but the second pass sets off the contrast between the intervallic stilted rhythmic material with the more flowing scalier material better. When I get to the sixteenth-note passage in measure 8, I breathe in beat two to keep the running sixteenths together. – just a thought…

The next section at rehearsal 1 is perhaps the toughest of the opening page with its’ range, large leaps, accidentals, etc. In my first pass I breathe after beats 1 in measures 10 and 12. My logic here is to try to maintain the architecture that is established in measure 4 where the phrase obviously begins on beat 2. In the second pass I breathe after beat 3 of the same measures so that beats 4 can serve as a pickup to the following measures. I had one teacher try to convince me to keep the octaves in measures 10 and 12 intact and breathe after them, but while it kind-of works in 10, I don’t care for it in 12. Remember, all these phrasing ideas are just suggestions. Take what you like, leave the rest.

The entrance pickup before rehearsal 2 is a tough one; coming in on a soft, low G after moments earlier wailing on a high C and B. (Honegger was obviously a string player!) Anyhow, a lot of players like to make the material between rehearsals 2 and 3 four (and sometimes five) phrases by breathing after the long notes in the middle of the two big phrases. I prefer to make this two phrases and only breathe in Honegger’s rests. Transition to firmer articulation and rhythm at rehearsal 3 to begin the set up for the Allegro at 34.

Set the Allegro section tempo at whatever rate you can triple-tongue the passage beginning at 116. (I’ve heard players put a slight ritard in 115 to accommodate their multi-tongue skill, but that’s not preferred.) Pay attention to note length values throughout this section. Honegger writes half-notes, quarter-tied-to-eighths and quarter-notes, I believe for a reason. The tendency at rehearsal 4 is to turn everything into half-notes and create a hemiola effect (2 over 3). While this is a weird section rhythmically, I don’t think 2 over 3 is what he was going for so observe what’s on the page.

I’ve included two different takes of the Maestoso to the end, that shows different breath options. I justify breathing after beats 2 in 155 and 156 to maintain the same shape the phrase begins with in 149. That being said, I think I prefer breathing on the barline at rehearsal 8.

Suggested Recordings

There are numerous recordings of this work, some of my favorites are: Hakan Hardenberger, Ole Edvard Antonsen, Wynton Marsalis. Eric Aubier’s recording is with an orchestral accompinament.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

Just heard of this piece yesterday from playwithapro.com. I’m looking around for new pieces to work out and this looks like a good one. Thanks for breaking this one down. I’ll probably be referring to this page a lot for this song. I can’t wait to get my copy.

can you tell me if the orchestral accompaniment or piano accompaniment came first? Did Honegger write both of them? Thanks, Marguerite